Living abroad for many years, one of the things which I came to realize and be impressed with, is how much American citizens give to charitable causes.

I was living in Hungary when the monster earthquake hit Haiti, and Hungarians were blown away to hear that average people in the United States were giving generously to help provide aid and relief for people they had never met in some faraway country. They were used to governments giving aid to regions with humanitarian crises, but for regular people to do such a thing was surprising to them.

It could be because people in the United States have more expendable income than people in most parts of the world, and that our currency is strong and goes further than other currencies. But that doesn’t detract from the fact that there is a culture here in the United States of using what we have to do good for other people.

Perhaps it comes from our history: having been a nation of immigrants, whose ancestors moved here to seek a better life or to escape poverty, and so it is built into our collective psyche, to use what we have to help others, knowing that we have experienced divine providential fortune to live in this country.

It also can’t be ignored, that a great number of Americans identify as ‘religious’. Part of the Judeo-Christian ethic is that, like Abraham, if we have been blessed, it is so we might be a blessing to others – that God wants to bless other people through us (Genesis 12:2).

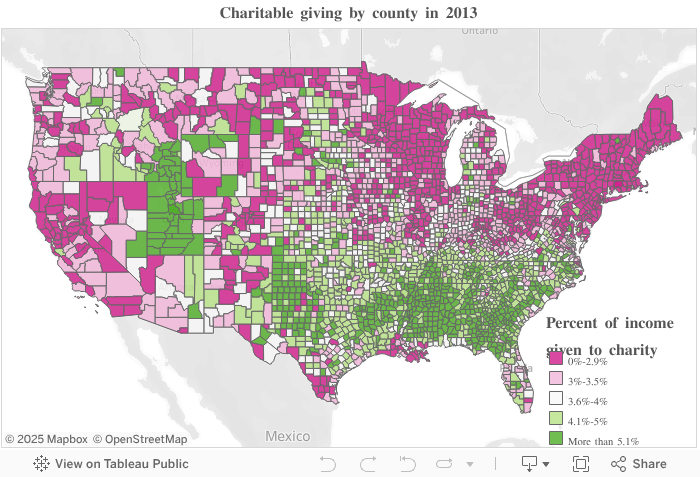

The Sacramento Bee published an article last month, showing the Adjusted Gross Income of every county in the US compared to how much was given in that county to charitable causes, non-profits and churches.

Interestingly, although perhaps not surprisingly, it was the poorer counties which gave more per capita than the richer ones. One of the major factors in how much people in a given county gave to charity seems to be religious affiliation; places with more people who attend religious services saw higher rates of charitable giving.

The idea that people who have less tend to give more may not be surprising to everyone. Jesus drew the attention of his disciples to a woman in the temple who gave her last 2 mites – all that she had, whereas other people who had more gave less of what they had. Preachers have long cited statistics which show the same thing: ironically, the more one accrues, the more miserly they tend to become with it.

How about Boulder County, Colorado, where yours truly is located? 2.6% of income was given to charity. That’s pretty low, and pretty ironic, because people in Boulder County, in my experience, talk a lot about being “locally minded and globally conscious” and caring about the well-being of other people, even if most of them are not Christian or attend religious services of any kind.

Neighboring Weld County was not much better at 2.7%, Larimer County came in at 3.2% (there are quite a few more church-going folks up there).

Here is the map with each county’s income versus charitable giving:

http://public.tableau.com/javascripts/api/viz_v1.js

Do you give charitably? The Bible recommends 10% of one’s income. The only places that came close to that number were the heavily Mormon populated counties of Utah.

Where do you direct your giving towards?